REPRODUCED – Rethinking P. A. Klier and D.A. Ahuja

By Carmin Berchiolly

Philipp Adolphe Klier (1845 – 1911) and D.A. Ahuja (c.1865-c.1939) are known for their prolific careers as photographers of colonial Burma. They were part of the early photographic-studio milieu, living in colonial Rangoon, and often competing for customers and employees.

Their stories intertwined multiple times, and eventually they encountered each other in a legal battle over copyright issues. Their businesses adapted to the growing demand in the postcard industry, and catered to foreign and local markets, a key element to their success.

Because these images were created by commercial photographers during the colonial period, we must rethink the original historical context that influenced their production. We must also consider the motivations behind the photographic practices of this time and how they ultimately helped the colonizing mission through the perpetuation of cultural stereotypes.

Klier’s Life and Business in Burma

From his arrival to Moulmein around 1870, Klier partnered with Heinrich Murken and ran the only business that offered photographic services. This partnership lasted until c.1875.Thereafter, Klier operated his own studio for about five years. He recorded historical events such as the Moulmein celebrations that were held when Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India on January 1st, 1877. He sent his work of this event to the Illustrated London News and The Graphic, both of which published illustrations based on his photographs in March of the same year. The Illustrated LondonNewsdescribed him as a “local artist of considerable repute”.

Based on photographic and advertising records, it is likely that Klier opened his own Rangoon studio sometime between 1877 and 1881, when he moved there with his family. Once established,Klier began a partnership with J. Jackson, who had run the only studio since c.1865. During his early years in Rangoon, Klier created multitude scenic views of Burma, as this photographic style was popular around the world during the 19thcentury. It was also during this time that he entered his work in competitions.In 1883-84 he earned a medal from the Calcutta International Exhibition.

Klier continued to expand his portfolio by making a short trip up north to photograph Mandalay in the second half of 1886, at the time of full British annexation of the country. By the following year, Klier was already advertising the views he obtained on the Rangoon Gazette & Weekly Budget. He advertised customizable options that buyers could make when creating their own albums of views and were available as Christmas cards.9 By the time of this advertisement, now in his forties,Klier had established a fully functioning business that allowed him to earn fame by his own merit and collect enough views to be a serious contender among other arriving photographers.By 1890, two new studios on Phayre Street had opened. Johnston & Hoffman of Calcutta, and H. H. Watts & F. A. E. Skeen.10 In the same year, the Klier-Jackson partnership dissolved for unknown reasons, and Klier began operating independently.His name as a Rangoon resident appeared inconsistently from 1894 to 1909.

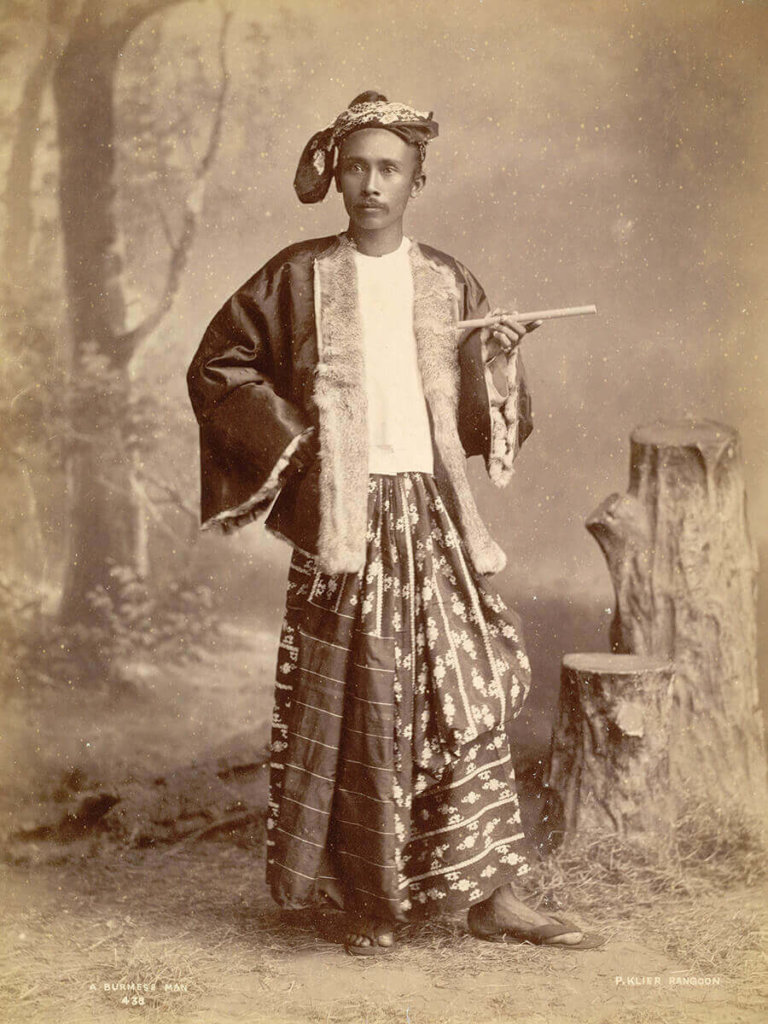

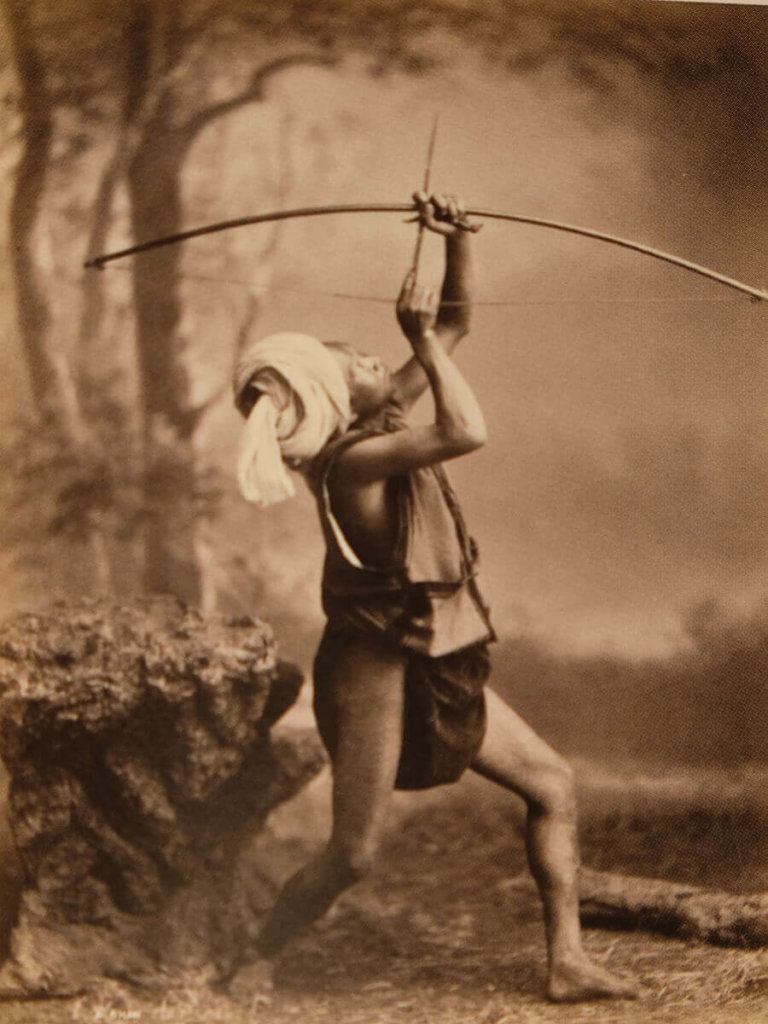

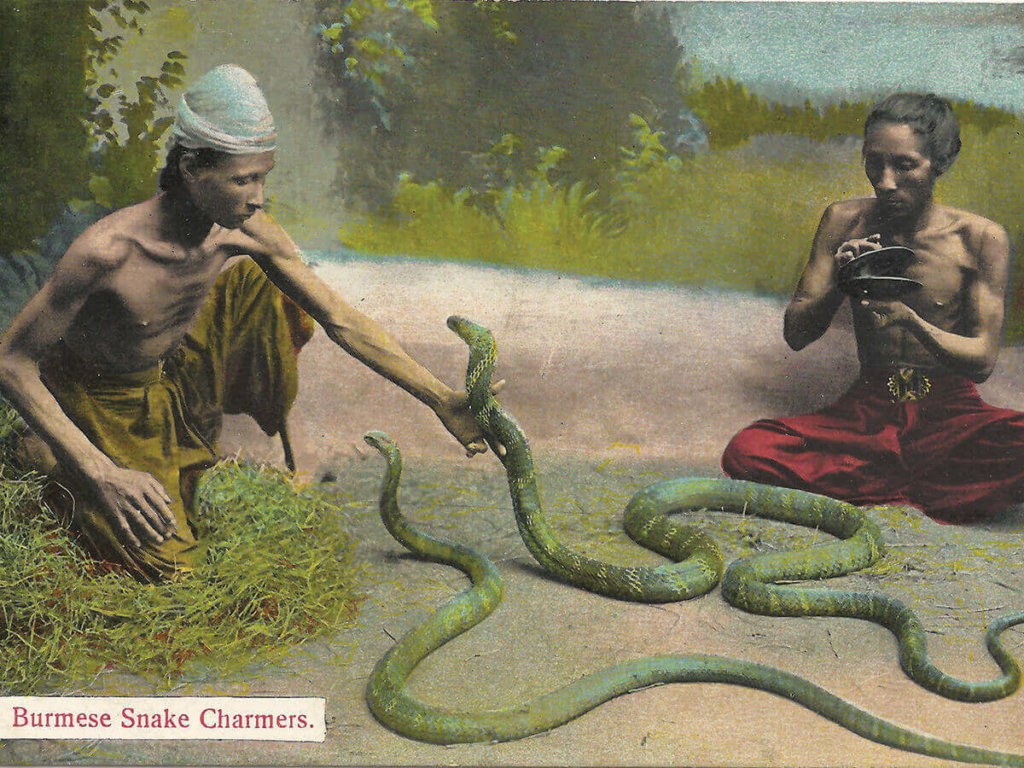

During the initial decades of his time in Rangoon, Klier produced a number of highly staged studio portraits that are well recognized and often reproduced in contemporary Myanmar culture. Many of the portraits were made to satisfy tourist interest in mailable postcards that could be obtained during travel to the country. The images sought to create a systematic record of the “types” of people that lived in Burma. However, the performative and staged aspects of his work become evident through visual analysis and allow viewers to rethink their readings and interpretations.

An example of this is found through the comparison of two images, which makes evident Klier’s use of the same model to present completely different stereotypes. The portraits are captioned “A Burmese Village Girl” number 510, and “A Burmese Lady” number 516. Based on the numeration system that Klier employed, both images were likely taken on the same day. In fact, the model’s hair style is the same in both portraits, showing the same flower and having the top bun slightly shifting on the left.

In the first portrait, Klier recreated a “village” scene by using a simple backdrop and plants heavily emphasized on the left. The “village girl” is posed standing on an angle and with her body in an active pose as she holds a large water jug. The model wears her hair styled with a top-bun and a flower. A plain undecorated semi-fitted cloth wraps around her body. The model wears her hta-meinpulled up to cover her bare breasts, reminiscent of the way some women in Burma wash their bodies in semi-public spaces. Perhaps this “village girl” is on her way to the river, to cleanse herself. The narrative that Klier constructed for this portrait depicts a lower-class girl, going about her day, and being comfortable in receiving the gaze of her viewer, as she stares back with a calm expression. The image is rare for its level of body-exposure when compared to the cumulative body of work from photographers working in Burma at this time. Although she is not nude, her bare shoulders and arms, and the form of her dress, present a different type of “Burmese woman” – one that is accessible. The differencehere is that the model is giving her attention back to us, sanctioning our gaze. This form of image allows for a form of objectification that was initially found in the “odalisque” type of portrait, and which becomes more evident in the next image.

The same model takes a different role in the “a Burmese Lady” portrait as a woman of elite status, albeit equally acceptingof the viewer’s gaze. Klier created a lavish scene with all the characteristics of an Orientalizing portrait. Draped tasseled textiles hang from above, creating an intimate interior, and serving as a framing device. An empty background allows us to focus completely on the model, who reclines comfortably on one side, expressing a lounging attitude with her long cheroot positioned to her side as she holds it casually. Props are abundant in this scene, with a paper fan, closed parasol, and flowers all fitted in a large vase with a luxurious fur laid as a type of table cover. The recliner used for the model is decorated with a textile reminiscent of Islamic geometric patterns, while the flower vase with its adorned surface depicting floral and animal motifs is aesthetically European. The model is dressed in traditional Burmese clothing and adorned jewels and floral hair decor. The juxtaposition of these incongruent objects, along with the position of the model’s body creates a composition that belongs in the Odalisque type, as popularized in French Orientalist painting and which promoted the freedom of the male gaze.

This important set of images allows us to determine that Klier’s portraits were highly manipulated visual representations of imagined stereotypes rather than honest captures of real people. While the degree of negotiation between the photographer and viewer existed, visual analysis provides strong evidence that an unequal and highly contrived relationship existed, a relationship that favored the photographer’s ability to manipulate while also allowing him to hold power and control of the final image for commercial use.

Klier began to sign his work in various ways, perhaps due to the increase in competition or as an incentive from the Indian copyright laws that were established in 1894. By the late 1880s to 90s he was embossing his signature on the bottom of his photographs. In some cases, he simply wrote “copyright”, without a signature. Most commonly, he wrote his name, a title for the work, and a number related to his series of views. Additionally, he began to experiment with various stamps with his name, some elaborately decorated and used to advertise on the back of his carte-de-viste, a practice that was quite popular at the time. These cards were produced and manufactured in Berlin and ranged in style, although evidence shows that he used multiple styles during the same year. He also began to produce his own postcards printed in Germany with the marking “‘Copyright’ P. Klier, Rangoon”.

Klier seems to have spent more considerable time photographing family commissions in his studio, as seen on his advertisements that show his availability for portraits. He was popular among European Rangoon residents and had costumers who commissioned their portraits from him more than once. Unlike his views of “Burmese characters”, these family portraits were produced for private use and were photographed with the established and popular visual conventions of European portraiture. The portraits also lacked the typical labels found in his tourist postcard series. These patrons belonged to the newly growing European bourgeoisie that settled in the new city of Rangoon.

Klier seems to have continued working until the last few years of his life, although his daughter Lizzie is listed as “asst. To P. Klier & Co.” on the “List of Residents” from 1906 to 1908. However, the business continued to expand and even added an additional location. Klier & Co. was a tenant of the Sofaer Building in Rangoon in the most prestigious office block in colonial Rangoon (now the Lokanat Gallery Building) that had strong links with the Jewish community. The status of the building was of such importance that the governor-general inaugurated the opening.

After Klier passed away, the business continued to operate at different locations. In 1912 Klier & Co. expanded to include Burmese curio sales of silverware, wood, and ivory carvings. It seems that even with the competition from Kodak’s portable cameras, there was still enough demand to keep the company open.16 By World War I (Jul 28, 1914 – November 11, 1918) Rangoon was still under British rule but ruled via Calcutta as a Province of India.Forced closures of Austrian and German firms, and the internment camps, likely led to the Klier family’s relocation to India.17 It appears, however, that Klier & Co. continued to operate after the war, as they remained listed yearly from 1918 to 1920.18These later listings do not indicate the extent of the business or who was managing it.

Klier’s descendants returned to Rangoon two years after the war, as mentioned in The Pioneer Mail and Indian Weekly News, which announced on February 1920 that a Klier couple and their two daughters had returned. This notice detailed various parties of Germans returning after being interned in India during the war. This family was likely Klier’s progeny and their children, assuming that he had a son who marriedand bore his own children while living in Rangoon.

The photographic collections created by Klier have ironically survived largely due to the reproduction of his work by the Ahuja photographic business, and other businesses and artists in contemporary popular media, making it easy for today’s consumers to forget to question the motivations behind such nostalgic imagery.

D.A. Ahuja meets Klier During the Postcard Craze

D.A. Ahuja & Co. was the largest manufacturer and distributor of postcards in colonial Rangoon. Because Klier was advertising his Christmas cards, which were mailed as a form of postcard, by at least 1886 and Ahuja claims to have been established in 1885, it is difficult to assess who initiated the practice in Rangoon. Although little is known about D.A. Ahuja’s personal life, by 1901 he was already prominent in the Rangoon community as evidenced by his publication of a photography manual published in Burmese.

Ahuja reproduced the works of many photographers including Klier and Jackson, Felice Beato, James Henry Green, and others. It was this practice of reproduction that led Klier to formally file a lawsuit against Ahuja, as he did not have permission or rights to reproduce and sell his photographic works. On September 19th, 1907, Klier appeared in court against Ahuja for using his images. The case was published on The Criminal Law Journal and on The Burma Law Reports.

Visual evidence of existing postcards supports Klier’s case against Ahuja. An example of this conflict is Klier’s photograph of a Burmese couple originally captioned “Burmese Man & Girl” (P.15) and marked with number 354, and the notice “REGD.”, which is the written abbreviation for “registered”. The original photograph used for this postcard has been dated to 1906.The registration mark is evidence of Klier’s concern over the use of his images but is a mark that is not found regularly on his existing work. The postcard version of this photograph produced by Klier, depicts the same image but has been modified with a tighter cropping and a coloring treatment. The postcard has also been given the marking “Copyright” P. Klier, Rangoon. 2 on the bottom of the front of the image.

The Ahuja reproduction used the same cropping. The coloring is nearly identical with some minor and nearly unnoticeable changes, mainly to the coloring of the grass and flowers.The Ahuja version also removed the Klier copyright notice and re-added the same caption with a different font and style. The back of the postcard is marked with “No 19. – D.A. Ahuja, Rangoon.” These images provide evidence that the practice of piracy existed during this time of high competition for business from the tourist market, and that the photographic milieu in Rangoon was brewing with complex relationships that were not void of civil conflict.

Even after court case, Ahuja and Klier continued to operate their businesses and appeared listed in various directories at the same time. These later listings show that the businesses continued but were under new management. By this time, Ahuja had also grown considerably in prominence and seems to have dominated the wholesale sector.

By 1908 Ahuja was still listing a studio at 47 Sule Pagoda Road. In 1910 he charged 2 annas for a postcard, twice the cost of a plate of rice and curry at the bazaar. Just a year later, in 1911, they described their selection as the largest of “pictorial postcards of Burma and India” and priced them at 8 annas per dozen. They also listed wholesale prices at Rs. 2/8 per 100 and Rs. 22/8 per 1,000.

One of the most popular “characters” in the postcards from this time was the depiction of “Burmese beauties”. As previously discussed, Klier recreated his own version of the odalisque, one that would be fitting in the Burmese context. This theme was also explored in Ahuja’s repertoire as the representation of women reclining privately in splendor and exuberance continued to fulfill the expected visual tropes.

An example of this is one of Ahuja’s many postcards titled “A Burmese Beauty”. A lavishly dressed and adorned woman lays on her side, greeting us with a smile as she holds a small flower on her hand. Her left hand rests on her slightly bent knees, revealing to us her bracelets and rings while drawing attention to the linear patterns on her skirt, and the floral patterns on the richly carved wooden recliner. The backdrop is painted with an outdoor scene that depicts lush flowers on the left side and a tall European style table on the far right. In this context, Ahuja’s Odalisques provoke an attitude of harmlessness and receptibility.

While it is difficult to assess which of the hundreds of postcards sold by D.A. Ahuja were actually his work, we must still critically consider their content. Susan Sontag notes that “there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.” Because the postcards are created from images that originated as photographs, their qualities transfer even after the change of medium.

The power that is granted to these images has brought forth myriad consequences in the colonial history of the country. The pervasiveness of the photograph reflects the pre-existingcondition of photography’s possessiveness and is further complicated when transformed into a postcard – a transferable commodity that can literally be possessed.

Ahuja’s entrepreneurial spirit allowed him to continue making a mark in the visual history of Burma. By 1917, the business had continued to flourish, expanded to multiple branches, and developed a large sales catalogue. The businesshad become internationally known through the International Trade Developer Annual.

Ahuja’s prominence by the 1920s was well know, as he took the portraits of important individuals.The Messengerdirectory listed him as having photographed a portrait in Rangoon of C. Jinarajadasa, the 4thpresident of the American Theosophical Society, in 1920. The sepia portrait was listed as available for purchase in the United States on a “nicely mounted card” for seventy-five cents. Also in 1920, T.N Ahuja, nephew of D.A., appeared for the first time on The British Journal Photographic Almanac, indicating that he was officially in partnership on this or the previous year.

By the following decade, it is evident that Ahuja continued to have strong links with the Rangoon community, and even a strong relationship with the police department. The Report on the Rangoon Town Policeshows that they paid Messrs. D.A. Ahuja & Co. for photographic services from 1926 to 1930. They continued to expand locally, and by 1936 the Times of India Annuallisted D.A.Ahuja as having a branch in both Rangoon and Mandalay.

There is a considerable gap in the archival records from 1930 to 1950, but it appears that they were still in operation throughout the years. The 1950 Rangoon: Sites and Institutionslists both D.A. and T.N. Ahuja as photographers,both having moved to separate addresses.32The businesses continued to operate through the 1950s and appeared somewhat regularly in different listings. In the 1954 Rangoon: A Pocket Guide, both D.A. and T.N. Ahuja are mentioned as photographers.

By 1959, The British Journal Photographic Almanacshows they were still operating in Mandalay. This year they also debuted the catch phrase: “Ahuja, the name that stands for leadership in every field of photo, cine, & x-ray services wholesale & retail.34 Attesting to their continued success for over seven decades.

Ahuja discontinued listing their businesses in The British Journal Photographic Almanacsometime between 1960 and 1964, coinciding with the 1962 dismantling of prime minister U Nu’s democratically elected government by the army Chief of Staff general Ne Win. On the 1962 Fodor’s Guide to Japan and East Asia, the Ahujas are recommended as the places for developing black and white film and Kodak Ektachrome type of film.35 By this time, the most successful photographic firm and wholesale in Rangoon seemed to have begun a short period of decline. However, in 2012, the last living photographer of the Ahuja family who was trained in traditional plate photography,was interviewed in The Old Photographer, a short film created by Thet Oo Maung. In the film, R.A. Ahuja recalls the times when his business, which was passed down to him from his father, T.N. Ahuja, was thriving during the Socialization period, attesting to the continued popularity and importance of photography in Burma.

The Ahuja family left an undeniable mark on how the country is seen and understood locally and internationally. During his career, D.A. Ahuja continued to foster Burma’s photographic production after he published his manual for amateurs. He trained some of the first local photographers that opened their own studios in the following years and even founded the country’s motion film industry. One of his well-known students was U Ohn Maung, who operated London Art Studio in the early twentieth century, one of the first Burmese-owned studios.Today, we can recognize that time as the beginning of a new era in the history of photography in Burma.

Carmín Berchiolly is a graduate of Northern Illinois University, DeKalb Illinois. She completed her M.A. in Art History with specialization in Southeast Asian and Museum Studies in 2018. She is currently the research assistant and program coordinator at NIU’s Center for Burma Studies, where she works closely with the Burma Art Collection, one of the most comprehensive art collections of Burmese Art outside of Myanmar. She is also the editorial assistant to the Journal of Burma Studies

h